Greece and Turkey tighten up Golden Visa rules: will Portugal follow?

The launch of Portugal’s Golden Visa (“GV”) scheme in 2012 has since boosted government coffers by more than EUR 6bln, with funds contributing to the revitalization of urban areas across the country. Once derelict property has been transformed – respectfully, and subject to strict planning laws – to create stunning apartment homes, hotels, and commercial buildings.

The city centers of Porto and Lisbon have been transformed. Tired-looking hotels in the Algarve have been rejuvenated into world class facilities. Major hotel chains are moving in; Hilton, Sheraton, 6Senses amongst others, and all stemming from investment raised via the country’s GV programme.

Evidently these schemes provide countries with a huge economic boost and growth opportunity, so why are they now being scaled back?

Last week, Greece’s PM, Kyriakos Mitostakis, announced the country’s minimum GV investment requirement would double from EUR 250k to EUR 500k. Prior to this, in June, Turkey increased its minimum GV investment from EUR 250k to EUR 400k. Meanwhile in the US, the minimum entry ticket has grown this year from USD 500k to USD 800k.

Likewise, Portugal toned down its own GV programme in 2021, by increasing the capital investment required as well as limiting the types and locations of property that are eligible for investment.

So, if they’re so popular, why make them harder to access?

Social and political pressures are clearly a major factor, as alluded to by the Greek PM during a televised speech on Saturday:

“In order to increase the affordability of real estate for Greeks, we are now increasing the minimum amount of investment required for the issuance of a Golden Visa from 250,000 euros to 500,000 euros”.

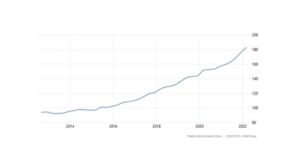

Portugal tells a similar story with residential house prices having increased at a consistently fast pace over the last 10 years.

And whilst a recent OECD study confers that house prices will continue to rise, it expects the nations’ average salaries, will not. The study finds that an average Portuguese person would require the equivalent of 11x annual earnings, to afford a small house!

Clearly there exist myriad pros and cons of GV schemes. An influx of foreign capital provides for much-needed infrastructure improvements as well as the renovation and repurposing of dilapidated but often beautiful, historic buildings. In turn this helps support the tourist industry and create jobs, particularly in depopulated areas, where local communities have been revitalized.

Of course, there is a flip side. If not implemented appropriately the social cost of rapid foreign investment and migration can have detrimental effects on the people it is primarily intended to benefit. If managed sensitively GV schemes can evolve to suit the changing social and economic environment, ensuring the local population reap the rewards of an enriched economy, rather than being over-exposed to negative effects such as the artificial driving up of housing costs, or lost communities and neighborhoods to hordes of tourists.

The Portuguese government frequently reviews its GV program with the intention of ensuring investment is spread proportionately across the country, into mixed-purpose projects and investment, not solely focused on residential. And (increasing) the minimum investment requirements are a means to deter all but the most committed HNW’s.

All GV schemes have a limited shelf life, at least in their original format, as they are constantly adapted to the prevailing social and economic environment. Whilst we are obviously big supporters of GV schemes as they cater to increasing demand for global freedoms of movement, governments need to ensure they are managed responsibly, ensuring local communities share in the benefits to the nation’s economy.

So, the real question that remains on everyone’s lips is not will Portugal place further restrictions on its GV scheme, but rather when?